Wednesday, April 18, 2012

amlodipine hypertension

Robert W. Morrow, MD: Thanks, Henry. I'm Bob Morrow, Associate Professor of Family and Social Medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. I have been in general family practice for 30 some-odd years -- mostly odd years. That's why we call it the borderline medical practice. I am also the Associate Director of Interventional Continuing Medical Education at the Center for Continuing Medical Education at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

The question I'm posing to you is one that has been puzzling to me. Having been brought up in the generation before calcium channel blockers (CCBs) got their big push as the expensive new guys on the block that weren't any better, I'm used to sticking with beta-blockers, thiazides, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors before going to CCBs as the second- or third-line drug, particularly in diabetic patients. Now we have a resurgence of the use of amlodipine. This is a drug that, in a good number of my patients, makes ankles swell. One of the reasons we treat blood pressure is to prevent heart failure and to prevent renal failure. Where does amlodipine fit in with all of that?

Dr. Black: Excellent question, and one that involves a little history. The first CCB or calcium antagonist was released in 1967, and it was verapamil. Over the years, CCBs have been lumped together because they block the entry of calcium into cells. In fact, every antihypertensive drug does that, directly or indirectly. We ought to view calcium antagonists as existing in 2 different flavors: non-dihydropyridines such as verapamil and diltiazem, and dihydropyridines, which are just about everything else. Verapamil and diltiazem slow heart rate, maybe improve insulin sensitivity, are not diabetogenic, and are pretty much metabolically neutral.

Dihydropyridines came along later, and they are very powerful antihypertensive drugs. In fact, amlodipine was originally in a study [in which it was administered at] 2.5 mg to 20 mg. At 20 mg, edema is invariable, so only 2.5 mg, 5 mg, and 10 mg are now currently available, but someone could take 2 if they wished. This is especially an issue for women, but not so much for men. I rarely go beyond 5 mg, but for women, I will often go to 10 mg.

Amlodipine has been the comparator drug in a large number of studies, including the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) and the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT). Amlodipine does very well when it comes to preventing problems, but it seems to cause heart failure, reasonably commonly. If a patient has heart failure, clearly you are not going to be using amlodipine. In the ALLHAT study, when it came to any number of issues, especially for stroke prevention, amlodipine was almost as good as chlorthalidone was.

The British recently stated in their National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines that, for individuals over 55 years of age or of any age if of African or Caribbean descent, either a thiazide-like diuretic or a CCB is the first drug of choice, and the second drug is an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker, with a diuretic after that. The NICE group's recommendation is probably the most evidence-based that we can see. They have the ability to look at enormous numbers of records through the National Health Service in Britain, and they have the ability to look at billions of bits of data, and that was their recommendation.

Amlodipine is an excellent drug for preventing strokes. In ALLHAT, glomerular filtration rates went up a little bit and stayed there, but people with renal disease didn't do worse. In the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) study, which compared amlodipine with metoprolol and ramipril, patients did fine on amlodipine if they did not have proteinuria. If they did have proteinuria with amlodipine, they stopped the treatment. Therefore, when somebody asks what I would give to a patient, what my first-choice drug would be, my question is always, "Tell me about the patient."

Dr. Morrow: Exactly.

Dr. Black: If the patient is an older African American who does not have heart failure or who might have angina or something else that a CCB would help, that's one thing. If the patient is a young, white individual who is asymptomatic, I'm not going to pick something like [amlodipine]. I think that's how we should approach each case.

Dr. Morrow: The New York State Medicaid Program's take on this, particularly the analytics from the State University of New York, is that we can't really distinguish between races. In some studies, race may have been poorly controlled. Also, you can't look at a person's degree of melanin and say that he is of this race, that race, or some other race. It becomes complex, and they don't suggest that you use it for your decision-making. I tend to agree with that. I will say that I frequently get into more trouble practically than I expect with the drug in terms of edema and development of what appears to be a decreased ejection fraction. I'm not convinced that it has a renal-protective mechanism that you would see over many years with an ACE inhibitor. Even knowing this new stuff, I tend to use amlodipine as number 3, and it would be good if we had more guidance from a national guideline. Do you know what is holding that up, or should we talk about that next time?

Dr. Black: We can talk about that next time. Thanks very much.

DIURETICS CHLORTHALIDON

Abstract

Background: Thiazide diuretics are cost-effective for the treatment of mild to moderate hypertension, but physicians often opt for more expensive treatment options such as angiotensin II receptor blockers or angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. With escalating health care costs, there is a need to elucidate the factors influencing physicians' treatment choices for this highly prevalent chronic condition. The purpose of this study was to describe the characteristics of physicians' decision-making process regarding hypertension treatment choices.

Methods: A comparative qualitative study was conducted in 2009 in the Canadian province of Quebec. Overall, 29 primary care physicians--who are also participating in an electronic health record research program--participated in a semi-structured interview about their prescribing decisions. Physicians were categorized into two groups based on their patterns of prescribing antihypertensive drugs: physicians who predominantly prescribe diuretics, and physicians who predominantly prescribe drug classes other than diuretics. Cases of hypertension that were newly started on antihypertensive therapy were purposely selected from each physician's electronic health record database. Chart stimulated recall interview, a technique utilizing patient charts to probe recall and provide context to physician decision-making during clinical encounters, was used to elucidate reasons for treatment choices. Interview transcripts were synthesized using content analysis techniques, and factors influencing physicians' decision making were inductively generated from the data.

Results: We identified three themes that differentiated physicians who predominantly prescribe diuretics from those who predominantly prescribe other drug classes for the initial treatment of mild to moderate hypertension: a) perceptions about the efficacy of diuretics, b) preferred approach to hypertension management and, c) perceptions about hypertension guidelines. Specifically, physicians had differences in beliefs about the efficacy, safety and tolerability of diuretics, the most effective approach for managing mild to moderate hypertension, and in aggressiveness to achieve treatment targets. Marketing strategies employed by the pharmaceutical industry and practice experience appear to contribute to these differences in management approach.

Conclusions: Physicians preferring more expensive treatment options appear to have several misperceptions about the efficacy, safety and tolerability of diuretics. Efforts to increase physicians' prescribing of diuretics may need to be directed at overcoming these misperceptions.

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

pancreas pancreatitis

From Medscape Education Gastroenterology

Breaking It Down: Improving Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Pancreatitis CME

CME Released: 04/02/2012; Valid for credit through 04/02/2013

View abbreviations used in this activity.

| Steven D. Freedman, MD, PhD: Hello, I am Dr Steven Freedman, director of The Pancreas Center and chief of the division of translational research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston. Welcome to this comprehensive update on chronic pancreatitis. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

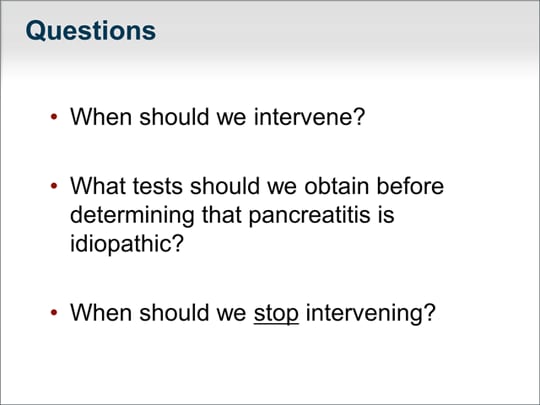

| Three important questions we must ask regarding the management of chronic pancreatitis are: When should we intervene? What tests should we obtain before determining that pancreatitis is idiopathic? And, importantly, when should we stop intervening? In medicine, we may become frustrated when we do not know the cause of a person's pain and obtain more tests. But it is important to know when to cease testing and how to address the patient's symptoms. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

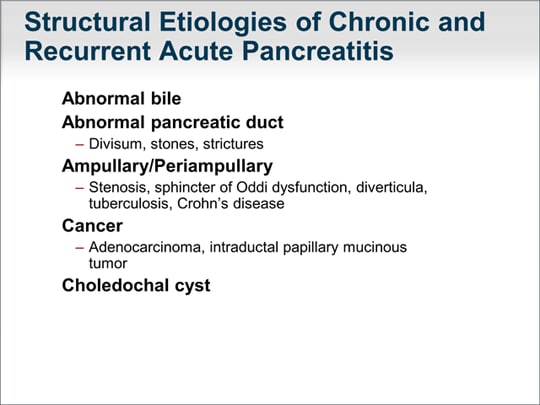

| Recurrent acute and chronic pancreatitis can have structural or nonstructural causes. Structural causes reflect an abnormality in the bile juice leading to the creation of biliary sludge or crystals. Abnormalities can occur in the pancreatic duct, as in pancreas divisum, which I will talk about shortly. Stones and strictures of the pancreatic duct can also occur. Other mechanical abnormalities, which can involve the ampulla of Vater, can lead to stenosis or sphincter of Oddi dysfunction as well as diverticula, tuberculosis, Crohn's disease, or cancer involving the ampulla of Vater or within the pancreatic gland. Cancer can be an adenocarcinoma, intraductal papillary mucinous tumor, or a neoplasm. Choledochal cysts also can cause recurrent acute and, rarely, chronic pancreatitis. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

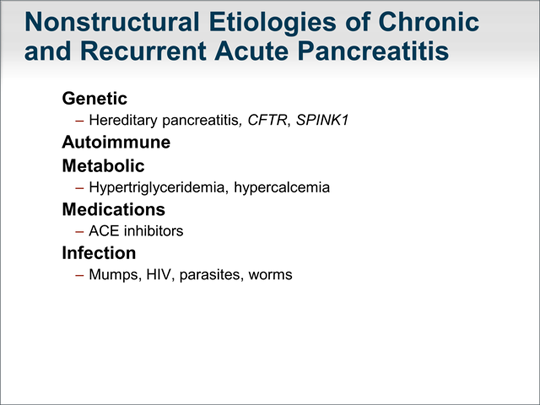

| Nonstructural causes include genetic abnormalities, which I will discuss in greater detail later. We are now realizing that autoimmune pancreatitis can result in recurrent acute episodes of inflammation of the pancreas but can also present as chronic pancreatitis. The diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis is informed by lab test results: immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) is abnormal in only approximately 30% to 40% of patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Tests for sedimentation rate, rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear antibody (ANA) may inform the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Imaging studies, especially MRI, can demonstrate characteristic features of autoimmune pancreatitis, which include rim enhancement, diffused edema of the pancreas, and irregularity of the pancreatic duct. Metabolic causes include hypertriglyceridemia that can lead to recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis and, also, chronic pancreatitis. Hypercalcemia can also be an etiologic factor. Generally, medications could be the cause of recurrent, acute episodes of pancreatitis but not chronic inflammation of the pancreas. Infection -- particularly infection related to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) -- can lead to inflammation of the pancreas. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

| Pancreas divisum is perhaps one of the more misunderstood causes of chronic or recurrent pancreatitis. Approximately 5% to [10%] of persons in the United States have pancreas divisum, but only a subset will develop pancreatitis. Many pancreatic specialists believe that only in very select situations, and perhaps more so in the pediatric population, is pancreas divisum an underlying cause of pancreatitis. In 2004, our group reported that an abnormality in the cystic fibrosis (CF) gene, CFTR, may be one reason why a subset of patients with pancreas divisum develop recurrent pancreatitis.[1] Pancreas divisum is not thought to lead to chronic pancreatitis, and the presence of pancreas divisum may be unrelated to a patient's pancreatitis; however, because many patients will have asymptomatic pancreas divisum, it is still important to determine whether the divisum is the cause of their pancreatitis. Sphincterotomy or other invasive procedures are often of no benefit to these patients. "Do nothing" is a more appropriate approach. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

| Incidence of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction in chronic or recurrent acute pancreatitis varies by researcher, from 15% to 86%. Pancreatitis in type 1 sphincter of Oddi dysfunction presents as classic postprandial pancreatic pain. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrates a dilated pancreatic duct with delayed emptying of contrast from the pancreatic duct. During an episode of pancreatitis, liver function blood test values as well as amylase and lipase counts are elevated. These results make sense because a sphincter of Oddi dysfunction should cause, at least, transient obstructions of both the biliary tree and the pancreatic duct system. The problem that we have realized over time is that sphincter of Oddi dysfunction may be a secondary problem and not the primary problem. For example, there have been reports of an underlying genetic abnormality causing inflammation of the entire pancreatic gland in patients with hereditary pancreatitis and a sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Sphincterotomy would not benefit these patients. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

| Let's now focus on genetic causes of chronic pancreatitis. Hereditary pancreatitis is autosomal dominant and, by definition, 2 or more family members are affected. Chronic pancreatitis is considered familial pancreatitis if only 1 other family member is affected. Hereditary pancreatitis has a relatively high penetrance rate of 80%. We tend to see this in patients in their early teens or as young as 5 or 6 years of age, but typically before age 20 years (although it can present at age 30 years or, rarely, by age 40 years). Its diagnosis is important because it is associated with a significantly increased risk of cancer of the pancreas, and patients can benefit from treatment and genetic counseling. The incidence of pancreatic cancer by age 70 years in patients with hereditary pancreatitis is 40%. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

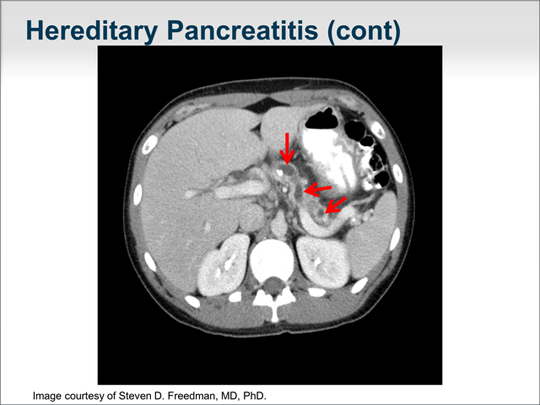

| Imaging studies typically demonstrate calcifications within the pancreatic duct as well as an irregular dilated pancreatic duct. Here is a typical CT appearance of a pancreas in a patient with hereditary pancreatitis. You can see the massively dilated pancreatic duct with calcifications. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

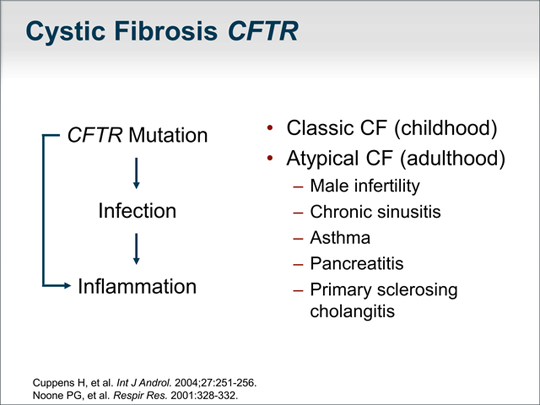

| Let's turn our attention to mutations in the gene responsible for cystic fibrosis, CFTR, a chloride channel that is in the apical plasma membrane of cells. An underlying defect in the CFTR gene causes the classic form of cystic fibrosis, in which median survival is now age 38 years.[2] It was thought that inflammation was secondary to the viscous secretions, especially in the lungs and airways, that lead to plugging and recurrent infection. It has become clear to many researchers that a mutation in that CF gene directly leads to an excessive host inflammatory response. This is important because a patient with a condition caused by an underlying defect in the CF gene is likely to have an excessive host inflammatory response and is prone to inflammation in an organ. Classic cystic fibrosis generally occurs in childhood and is caused by 2 defective genes. However, we have also identified atypical cystic fibrosis in which a person can have a mild mutation or be just a carrier of a CF gene mutation. Atypical cystic fibrosis presents as infertility in males -- the male reproductive tract is the most sensitive to a CF gene defect; approximately 40% of cases of infertility in males is due to an underlying defect in the CF gene.[3] Other groups have found that up to 40% of patients with recurrent or chronic sinusitis have an underlying mild CF gene defect, which also may be true in the case of asthma. A number of papers -- including some from our group -- report that patients who are carriers of a CF gene mutation and who have underlying colitis due to inflammatory bowel disease are those who are at risk for developing primary sclerosing cholangitis.[4] |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

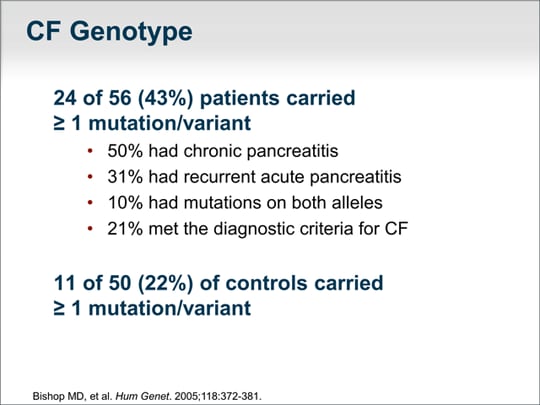

| One of the most comprehensive studies of the CF genotype and its relationship to recurrent acute or chronic pancreatitis in both children and adults found that 43% of patients carried at least 1 mutation or variant.(Mutation refers to a change in the gene sequence that we know causes disease, whereas variant is a change in the gene sequence that we are not certain results in disease.) In that study, 50% of patients with chronic pancreatitis and 31% in patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis had at least 1 mutation or variant. Ten percent of patients had mutations on both alleles, and 21% met the criteria for the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis based on the CF foundation consensus definition. Overlooked by many investigators and clinicians is the fact that 22% of healthy persons also carry 1 mutation or variant. This is nearly double the rate of genotype abnormalities in patients with pancreatitis. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

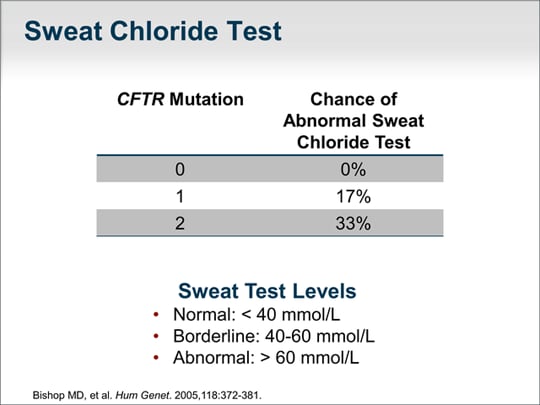

| Sweat chloride testing is a functional measure of the CFTR gene chloride channel. A person without a CFTR mutation would have a normal sweat chloride test result. Less than 40 mmol/L is normal. Importantly, 40 to 60 mmol/L may or may not reflect a defect in the CFTR chloride channel. One mutation implies a 17% chance of having an abnormal sweat test result and 2 mutations double the risk.Overall, approximately 9% to 10% of patients in this study had an abnormal sweat test result. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

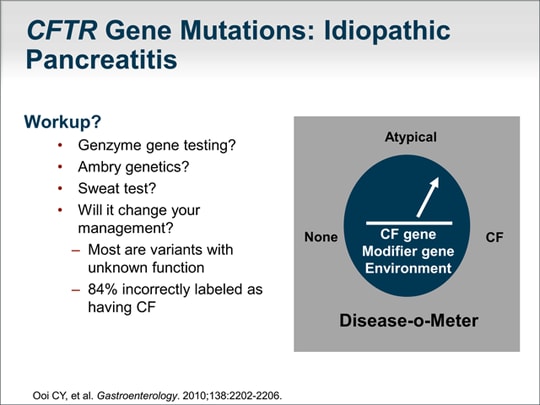

| For most diseases, we know that whether a person will develop a disease does not depend on a single gene abnormality, but on a modifier gene as well as environmental factors. In this discussion, the gene of primary interest is the CFTR gene. A modifier gene that I will talk about is the SPINK1 mutation. An environmental factor could be having a glass of wine daily. So, a person has a CFTR gene abnormality, is a carrier, drinks a glass of wine every day, and may have SPINK1 mutation: Is that enough to predict that the patient will develop chronic pancreatitis? It could be. There appears to be confusion in the literature regarding the appropriate workup for the CFTR gene abnormality. Limited gene tests -- such as the Genzyme CF87 gene screen or the typical in-hospital 36-gene screen -- only test for gene mutations that lead to the classic form of cystic fibrosis. Those gene mutations are unlikely to be present in a patient who does not have cystic fibrosis but who has chronic or recurrent pancreatitis. Those tests will not be helpful. The clinical significance of the results of exhaustive full gene sequencing is unknown, and many health insurance companies no longer cover those tests. What is important is whether the results of a test will change your disease management, and, for this reason, it is generally recommended that a functional measure of the CFTR gene be obtained, and that is a sweat test, which is inexpensive and noninvasive. We know that most variants picked up on a full gene screen have unknown function. A paper published in 2010 demonstrated that 84% of patients were incorrectly thought to have cystic fibrosis based on extensive gene sequencing. The current recommendation is that patients thought to have an underlying CF gene abnormality should undergo a sweat test. The rationale for that recommendation is to determine whether the consensus statement guidelines for the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis are met. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

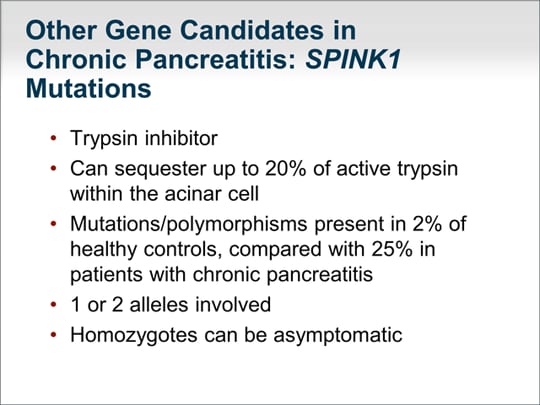

| The next gene I would like to talk about is SPINK1, a trypsin inhibitor that can sequester as much as 20% of active trypsin within the acinar cell. The problem is that mutations and polymorphisms are present in 2% of healthy controls, although these abnormalities are present in about 25% of patients with chronic pancreatitis. One or 2 alleles can be involved, but homozygotes can be asymptomatic. SPINK1 is thought to be a modifier gene; even if you are homozygous for SPINK1 mutation, you may not have pancreatic disease whatsoever. Thus, looking for mutations in SPINK1 is unlikely to have any clinical consequence. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

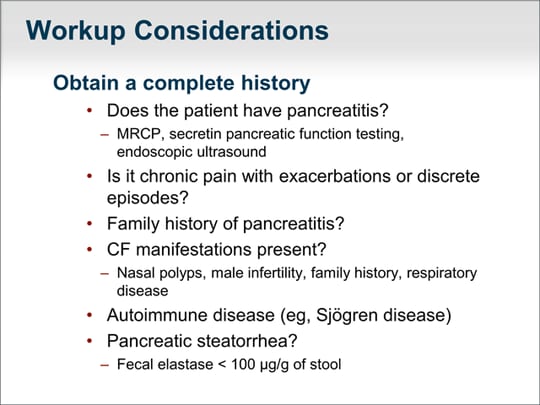

| Let's step back and think about the overall workup. Does the patient actually have pancreatitis or some other chronic abdominal pain unrelated to the pancreas? The history is important. What studies are needed? Do we need a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), secretin pancreatic function testing, or endoscopic ultrasound? All of these tools may help sort out whether the patient truly has chronic pancreatitis. Is there a family history of pancreatitis that would suggest hereditary pancreatitis? Do other manifestations suggest a CF gene problem? Does the patient have nasal polyps, male infertility, family history of cystic fibrosis, or a significant respiratory disease or sinusitis that would prompt a further workup? Does the patient have an autoimmune disease to suggest the possibility of autoimmune pancreatitis? What might help focus the workup for pancreatitis is whether the patient has pancreatic steatorrhea. Although this determination can be based on clinical findings, a fecal elastase value of less than 100 µg/g of stool is highly suggestive of steatorrhea. If the patient has steatorrhea, longstanding chronic inflammation and progressive destruction of the pancreatic gland are likely. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

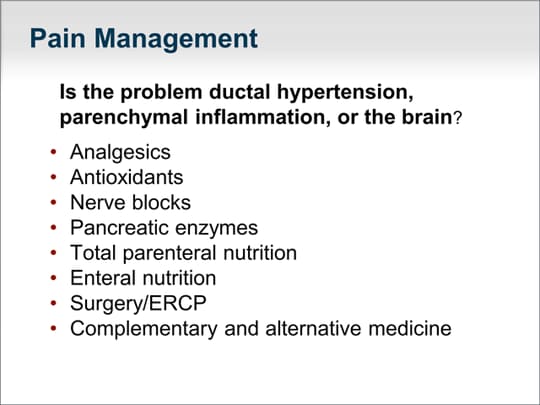

| How do we address the chronic pain, nausea, and frequent vomiting that are the salient features of chronic pancreatitis? We must first determine whether the patient has an obstructed pancreatic duct system. Pancreatic ductal hypertension can be treated with endoscopic or open sphincterotomy. Do they need a Puestow procedure? Is it a diffuse parenchymal inflammatory problem, as one would see in idiopathic chronic pancreatitis related to the CFTR gene? Or is the patient's brain reinforced to the sensation of chronic pain that it is now a central nervous system problem that we have to address? Analgesics are used often, although we try to minimize the use of narcotics. Antioxidants may be helpful. Nerve blocks such as a celiac nerve block are generally not helpful, even if performed with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guidance. Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy is helpful in the treatment of pain, but only the quick-release preparations, which are currently not FDA-approved in the United States. Resting the pancreas can be helpful, especially in patients who have postprandial pain. A 3-week course of total parenteral nutrition via a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line or enteral nutrition through a J-tube can be helpful. Interventions such as surgery and ERCP should be undertaken only after careful consideration of whether the results would have an effect on the patient's outcome. Complementary and alternative approaches have a major role. As most gastroenterologists and internists are aware, many of our therapies for chronic pancreatitis are not very effective, and approaches such as meditation, acupuncture, yoga, and other mind-body therapies can have an effect on this disease. Many patients are depressed because of their chronic pain, and addressing psychosocial issues is an important aspect of caring for the whole patient with chronic pancreatitis. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

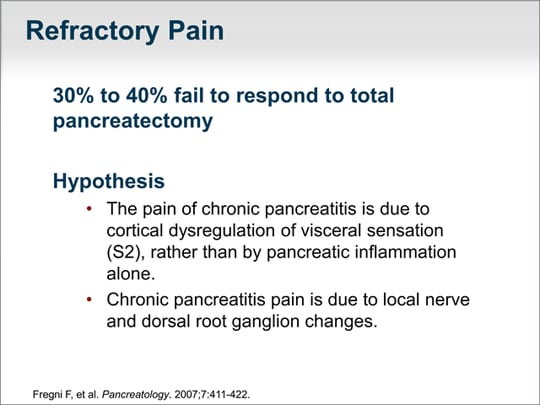

| What do we do for refractory pain? We know that 30% to 40% of patients have no improvement in their pain even after total pancreatectomy. That tells us that there are changes either in the nerves to the spinal column or in the brain. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

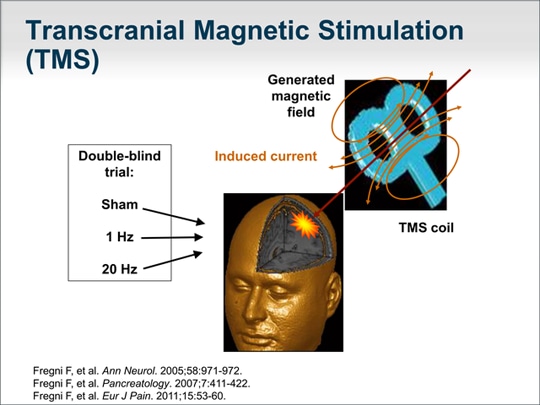

| Our group has published on a novel noninvasive approach called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for the treatment of pain from chronic pancreatitis. I mention this to highlight that the pain experienced in chronic pancreatitis is complex and likely to require multiple modalities. Our studies found that applying a very focused beam of magnetic stimulation to the cortical S2 region of the brain ameliorated the pain in approximately 70% of patients with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis.[5] Although the technique is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression, it remains experimental for the treatment of pain associated with chronic pancreatitis. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

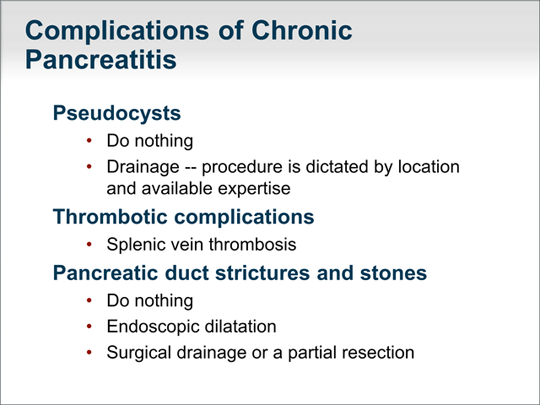

| Let's now focus on the complications of chronic pancreatitis. Pseudocysts are a common complication, and although we always feel compelled to intervene when we see a large pseudocyst, doing nothing is often the appropriate course. A pseudocyst should be drained only if is rapidly expanding and causing symptoms, about to invade blood vessels, or clearly infected. The drainage procedure is dictated by the location of the pseudocyst as well as the available personnel and equipment to perform the procedure. Thrombotic complications such as splenic vein thrombosis are occasionally seen. Management of pancreatic duct strictures and stones is controversial. Many strictures and stones seen in chronic pancreatitis are sequelae of chronic inflammatory changes. When they are not the cause of the inflammation, doing nothing is often the best course. Occasionally, endoscopic dilatation of a pancreatic duct stricture or removal of stones is helpful, such as when the lesion obstructs pancreatic outflow to the duodenum. The same applies to surgical interventions where, again, surgical drainage or a partial resection can be beneficial. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

| Management of pancreatic insufficiency is usually relatively straightforward. The diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is made on a clinical basis, by laboratory tests, or both. Patients with pancreatic steatorrhea will have a very specific type of diarrhea that is pale, oily, and greasy. An important clinical pearl is that the stool sticks to the walls of the toilet bowl and is very difficult to flush away. Generally, steatorrhea is made worse by ingestion of fats. Significant improvement with pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in a patient with this clinical description is sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. When the diagnosis is less clear, we turn to fecal elastase values. A fecal elastase value greater than 200 µg/g of stool is normal, whereas 100 to 200 µg/g is a gray zone, and less than 100 µg/g is essentially diagnostic of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. The value of fecal elastase testing is that it measures the concentration of pancreatic elastase per gram of stool, which is why no specific diet is required and why a random stool sample can be used for the test. A patient on pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy should not use it for at least 4 days before a stool sample is obtained to measure fecal elastase. Treatment is typically a diet that is lower in fat, in addition to pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy. The pancreatic enzyme capsules mimic the normal secretions of the pancreas in response to a meal. Patients should take their dose with the first bite of a meal or in the middle of the meal so that the enzymes mix fully with the meal and digest the substrates to be absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

| I want to talk about emerging therapies. There are novel pancreatic enzymes that are more effective that are currently in testing. As of January 2012, a drug has been approved to correct the underlying cystic fibrosis protein G551D mutation abnormality. It is hoped that this is the beginning of therapies to ameliorate diseases related to defects in the cystic fibrosis gene. There have also been a number of trials recently on nerve growth factor monoclonal antibodies or antagonists. Because the pain of chronic pancreatitis is mediated in part through nerve growth factor, these represent attractive potential therapies to treat the pain of chronic pancreatitis. We await results of phase 3 trials. I have mentioned TMS and complementary and alternative medicine approaches as well. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

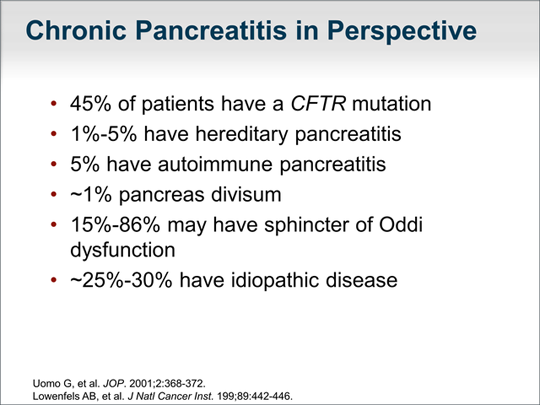

| Important in guiding our workup of chronic pancreatitis is the knowledge that approximately 45% percent of patients with chronic pancreatitis will have a mutation in the CFTR gene. From my clinical observations, approximately 1% to 5% will have hereditary pancreatitis and 5% will have autoimmune pancreatitis. Perhaps 1% of patients will have pancreas divisum and 15% have sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (although this may be an overestimation). Approximately one third of cases of chronic pancreatic are idiopathic. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

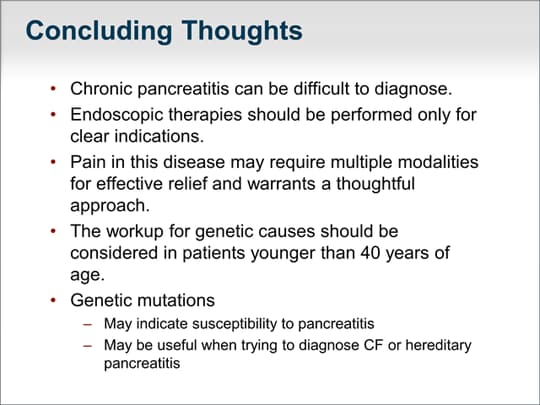

| Chronic pancreatitis can be difficult to diagnose. Endoscopic therapies should be performed only for very clear indications and not just for chronic pain that fails to respond to conventional approaches. The pain in this disease requires a thoughtful approach, which may include multiple modalities for effective relief. Referral to a pain clinic or a pancreatitis specialty center that employs a multidisciplinary approach that includes a pancreatic surgeon, pancreatic endoscopist, and pancreatologist may be warranted to determine the optimal management. The workup for genetic causes should be considered in patients younger than 40 years and it is important to understand that genetic mutations may simply indicate a susceptibility to pancreatitis. I urge caution if you perform genetic testing and give a patient a diagnosis of, for example, cystic fibrosis; just because a patient has a variant or is a carrier of a CF gene mutation does not establish the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Remember that cystic fibrosis has a number of insurance ramifications and psychosocial implications and carries with it a shortened life expectancy. Genetic testing can be helpful if you are trying to explain why a patient has chronic pancreatitis. Patients with a genetic abnormality generally will not benefit from surgical or endoscopic approaches. |  (Enlarge Slide) (Enlarge Slide) |

Thank you for participating in this activity. To proceed to the online CME test, click on the earn CME link.

statins dementia

Recently, statins have been shown to possess potent anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects, which fueled the hypothesis that statins could be neuroprotective agents, Dr. Gao and colleagues note in their report. Yet, prospective and epidemiologic studies to date have generated mixed results regarding statin use and PD risk, and the overall evidence for benefit "remains unconvincing," they say.

The researchers caution that their analysis has several limitations. Chief among them is the fact that they classified use of any cholesterol-lowering drugs before 2000 as statin use; as a result, misclassification was "inevitably introduced," they say. However, based on US retail prescription data, statins accounted for 72% of total cholesterol-lowering drug use in 1994, 80% in 1996, and more than 90% in 2000.

The lack of information on which specific statin drugs were used is another limitation. "We would like to test the effects of each specific statin as their ability to enter the brain varies and so they may have different effects on PD," Dr. Gao commented.

For example, lovastatin and simvastatin have been shown to have more potency to cross the blood-brain barrier relative to atorvastatin calcium. The researchers say it is likely that their results are driven by these 2 statins given that they were the most commonly prescribed in the mid-1990s.

The authors say they cannot exclude residual confounding because of the observational nature of the study.

Clearly more study is warranted, the researchers conclude, not only because statins may have neuroprotective effects, but also because they may have unfavorable effects by lowering the level of plasma coenzyme Q10, which may itself be neuroprotective in PD.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Gao has been a consultant for Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Arch Neurol. 2012;69:380-384. Abstract

Saturday, April 07, 2012

dementia

"Silent" Cerebral Emboli May Hasten Progression of Dementia

This finding was noted both in patients with Alzheimer disease and those with vascular dementia.

Patients with Alzheimer disease (AD) often exhibit vascular changes in the brain. In this study, U.K. researchers used transcranial Doppler ultrasonography of the middle cerebral artery to determine the prevalence of spontaneous cerebral emboli in 84 patients with AD and 60 patients with vascular dementia. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography was performed every 6 months for 18 months, and changes in cognition, behavior, and functional status were tracked by standardized assessment tools over a 2-year period.

Spontaneous cerebral emboli were detected in 43% of patients with AD and 45% of those with vascular dementia. Scores on every assessment scale showed greater deterioration in patients with emboli than in those without, and the effect of emboli on progression of dementia was similar in patients with AD and those with vascular dementia. Mean decline on the 30-point Mini-Mental State Examination was 6.9 points in emboli-positive patients and 3.4 points in emboli-negative patients; mean change on the 70-point Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive was 15.4 and 6.0 points, respectively. Few AD patients had internal carotid stenosis or previous strokes.

Comment: These provocative results suggest that vascular disease — as reflected by Doppler-detected asymptomatic cerebral emboli — is a factor in the progression of AD. In fact, an editorialist believes that the dichotomy between AD and vascular dementia has been overstated. The next steps are to figure out the source of these emboli and to determine whether therapies directed against atheromatous disease and thrombosis can slow the progression of AD; unfortunately, a recent study found statin therapy to be ineffective in this regard (JW Gen Med Aug 30 2011).

Published in Journal Watch General Medicine April 5, 2012