Saturday, December 30, 2006

aspirin plus persantin (dipyridamole)

- 1: Lancet. 1989 Jul 1;2(8653):1-7.

-

- Comment in:

- Lancet. 1989 Aug 19;2(8660):443.

Trial of low-dose aspirin plus dipyridamole versus anticoagulants for prevention of aortocoronary vein graft occlusion.

Division of Cardiology, University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland.

In a prospective randomised trial, 249 patients who had aortocoronary vein bypass surgery were assigned either to a platelet inhibitory drug regimen or to standard anticoagulant therapy. Treatment was replaced by placebo in half of the patients in each group after 3 months. The platelet inhibitory drug regimen--very low-dose aspirin combined with dipyridamole--was as effective as standard anticoagulant therapy to prevent early and late graft occlusion. Death, myocardial infarction, and severe bleeding occurred significantly more often in patients receiving anticoagulants, whereas mild drug-related gastrointestinal and cerebral side-effects were more common in patients taking platelet inhibitory drugs. Antithrombotic treatment should be continued for at least 1 year after coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

PMID: 2567792 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

as[irin en persantin

- 1: Eur Heart J. 1994 Aug;15(8):1129-34.

-

Effect of various antithrombotic regimens (aspirin, aspirin plus dipyridamole, anticoagulants) on the functional status of patients and grafts one year after coronary artery bypass grafting.

Department of Cardiology, Academic Medical Centre Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

From 1987 until 1991 a large prospective randomized multicentre study was performed in The Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland entitled CABADAS (Prevention of Coronary Artery Bypass graft occlusion by Aspirin, Dipyridamole, and Acenocoumarol/Phenprocoumon Study). The aim of CABADAS was to evaluate the relative efficacy of (1) aspirin, (2) aspirin plus dipyridamole, and (3) oral anticoagulants in the prevention of vein graft occlusion during the first year after aortocoronary bypass surgery. No significant difference was observed in the incidence of graft occlusion among the three treatment groups. In a subgroup of 127 CABADAS patients, studied in the Academic Medical Centre in Amsterdam, the relationship between treatment and clinical status (i.e. symptoms of angina pectoris and exercise capacity) was assessed, and the relationship between treatment and functional status of the vein grafts was determined by means of thallium-201 exercise scintigraphy. There were no differences in symptoms among the three treatment groups in the 127 patients studied. There were no significant differences either among the treatment groups, as regards exercise capacity and the number or intensity of perfusion defects, in the 81 patients who underwent thallium-201 exercise scintigraphy. The three antithrombotic treatment regimens had a similar effect on the clinical status of patients and on the functional status of venous bypass grafts one year after coronary bypass surgery. This finding underscores the CABADAS results in that aspirin may be the preferred treatment option in patients following venous bypass surgery.

PMID: 7988607 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

aspirin en persantin

- 1: J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994 Nov 1;24(5):1181-8.

-

Effects of low dose aspirin (50 mg/day), low dose aspirin plus dipyridamole, and oral anticoagulant agents after internal mammary artery bypass grafting: patency and clinical outcome at 1 year. CABADAS Research Group of the Interuniversity Cardiology Institute of The Netherlands. Prevention of Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Occlusion by Aspirin, Dipyridamole and Acenocoumarol/Phenprocoumon Study.

Department of Cardiology, University Hospital, Groningen, The Netherlands.

OBJECTIVES. This study was performed to compare the efficacy and safety of aspirin, aspirin plus dipyridamole, and oral anticoagulant agents in the prevention of internal mammary artery graft occlusion. BACKGROUND. Antithrombotic drugs increase vein graft patency after coronary artery bypass surgery. Their benefit after internal mammary artery grafting has not been established. METHODS. Angiographic internal mammary artery graft patency at 1 year was assessed in 494 patients who received both internal mammary artery and vein grafts. These patients were a subgroup of a prospective, randomized vein graft patency study in 948 patients assigned to treatment with aspirin, aspirin plus dipyridamole, or oral anticoagulant agents. The design was double-blind for both aspirin groups and open for oral anticoagulant treatment. Dipyridamole (5 mg/kg body weight per 24 h intravenously, followed by 200 mg twice daily) and oral anticoagulant agents (prothrombin time target range 2.8 to 4.8 international normalized ratio) were started before operation, and low dose aspirin (50 mg/day) after operation. Clinical outcome was assessed by the incidence of myocardial infarction, thrombosis, major bleeding or death. RESULTS. Occlusion rates of distal anastomoses were 4.6% in the aspirin plus dipyridamole group and 6.8% in the oral anticoagulant group versus 5.3% in the aspirin group (p = NS). Overall clinical event rates were 23.3% and 13.3% in the aspirin plus dipyridamole group and the aspirin group, respectively (relative risk 1.75, 95% confidence interval 1.09 to 2.81, p = 0.025), and 17.1% in the oral anticoagulant group. CONCLUSIONS. Internal mammary artery graft patency at 1 year is not improved by aspirin plus dipyridamole or oral anticoagulant agents over that obtained with low dose aspirin alone. However, there is evidence that the overall clinical event rate increases if dipyridamole is added to aspirin.

PMID: 7930237 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

-

Related Links

- Prevention of one-year vein-graft occlusion after aortocoronary-bypass surgery: a comparison of low-dose aspirin, low-dose aspirin plus dipyridamole, and oral anticoagulants. The CABADAS Research Group of the Interuniversity Cardiology Institute of The Netherlands. [Lancet. 1993] PMID: 8101300

- Effect of various antithrombotic regimens (aspirin, aspirin plus dipyridamole, anticoagulants) on the functional status of patients and grafts one year after coronary artery bypass grafting. [Eur Heart J. 1994] PMID: 7988607

- Worse clinical outcome but similar graft patency in women versus men one year after coronary artery bypass graft surgery owing to an excess of exposed risk factors in women. CABADAS. Research Group of the Interuniversity Cardiology Institute of The Netherlands. Coronary Artery Bypass graft occlusion by Aspirin, Dipyridamole and Acenocoumarol/phenoprocoumon Study. [J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999] PMID: 10577567

- Trial of low-dose aspirin plus dipyridamole versus anticoagulants for prevention of aortocoronary vein graft occlusion. [Lancet. 1989] PMID: 2567792

- A comparison of internal mammary artery and saphenous vein grafts after coronary artery bypass surgery. No difference in 1-year occlusion rates and clinical outcome. CABADAS Research Group of the Interuniversity Cardiology Institute of The Netherlands. [Circulation. 1994] PMID: 7955195

- See all Related Articles...

combinatie aspirine en persantin

Among patients with recent stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), combined therapy with clopidogrel plus aspirin has not been proven better than aspirin alone. But what about dipyridamole plus aspirin? A large trial published in 1996 suggested that this combination was more effective than aspirin alone, but other trials have produced conflicting findings. In the new ESPRIT trial, researchers randomized more than 2700 patients with recent stroke or TIA to receive either aspirin plus dipyridamole (200 mg twice daily) or aspirin alone. No placebo was used. During an average follow-up of 3.5 years, significantly fewer patients assigned to combination therapy than to aspirin alone experienced vascular death, nonfatal stroke, MI, or major bleeding (13% vs. 16%). A meta-analysis of this and five similar dipyridamole-aspirin studies showed an 18% relative risk reduction with combination therapy compared to aspirin alone (Journal Watch Jun 9 2006).

Clopidogrel appears to be a useful adjunct to aspirin therapy in patients with acute coronary ischemia and patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, but it should not be used with aspirin in other patients at cardiovascular risk. For patients who have had strokes or TIAs, aspirin plus dipyridamole may be the preventive treatment of choice.

— Bruce Soloway, MD

Published in Journal Watch General Medicine December 28, 2006

Thursday, December 28, 2006

rate and rhythm controle

atrial fibrilation

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wednesday, December 27, 2006

anticoagulants

| Terutroban and endothelial TP receptors in atherogenesis] | |

| Tony J Verbeuren | |

| Treatment of thrombotic diseases implicates the use of anti-platelet agents, anti-coagulants and pro-fibrinolytic substances. Amongst the anti-platelet drugs, aspirin occupies a unique position. As soon as it became evident that the major action of aspirin is indirect blockade, through inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX), of the production of thromboxane A2 (TXA2), a powerful vasoconstrictor and platelet activator, research for new anti-thrombotics that interact more specifically with the production and/or the action of TXA2 was started. Terutroban (S 18886) is a selective antagonist of TP receptors, the receptors for TXA2, that are present on platelets and on vascular smooth muscle cells, but also on endothelial cells. The role played by the platelet and smooth muscle cell TP receptors in thrombotic disease is well known, and preclinical and clinical studies with terutroban have illustrated the powerful antithrombotic effects of this agent. The implication of endothelial TP receptors in the development of atherosclerotic disease has only been examined during the past five years and studies with terutroban have been crucial for understanding the role of these endothelial receptors in cardiovascular physiopathology. The goal of the present review is to discuss the arguments in favour of the hypothesis suggesting that activation of endothelial TP receptors, by causing expression of adhesion molecules, favours adhesion and infiltration of monocytes/macrophages in the arterial wall, thereby stimulating the development of atherosclerosis. The review will also highlight the important contribution of the studies performed with terutroban in this research area. The triple activity (anti-thrombotic, anti-vasoconstrictor, anti-atherosclerotic) observed with terutroban in preclinical studies, stressed by the first results in clinical development, places terutroban as an innovative drug with a unique potential for treatment of cardiovascular disorders. | |

| Can J Cardiol. 2006 Feb ;22:149-51 |

alendronate (bifosfanaat)

Stopping Alendronate After 5 Years Seems Safe for Most Women

Women who stopped taking alendronate appear after 5 years to maintain bone mineral density compared with those who continue taking the drug, researchers report in JAMA. Some 1100 women who had been on the drug an average of 5 years were randomized to another 5 years' treatment with the drug or with placebo. Bone mineral density was measured at randomization and then annually thereafter. Total-hip BMD was the primary end point. The women continuing alendronate maintained a higher BMD, relative to those switching to placebo, but the difference was only 2% to 3%. The risk for nonvertebral fractures did not differ significantly between the two groups, but the risk for vertebral fractures was higher in the women who discontinued alendronate. Women at high risk for vertebral fractures ought to be considered for continued therapy, the authors suggest. An editorialist agrees that, otherwise, most women "can consider a 'holiday' period of up to 5 years without therapy."

JAMA article (Free abstract; full text requires subscription)

JAMA editorial (Subscription required)

Saturday, December 23, 2006

melk en colonkanker

In the Cohort of Swedish Men, 45 306 men aged 45 to 79 years and without a history of cancer completed a food-frequency questionnaire in 1997 and were followed up through December 31, 2004.

During a mean follow-up of 6.7 years, 449 incident cases of colorectal cancer occurred. After adjustment for age and other risk factors, the multivariate rate ratio (RR) of colorectal cancer for men in the highest quartile of total calcium intake compared with those in the lowest quartile was 0.68 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51 - 0.91; P for trend = .01).

High dairy consumption was also associated with a lower risk for colorectal cancer. Colorectal cancer risk for 7 servings/day or more of total dairy foods was about half that for less than 2 servings/day (multivariate RR, 0.46; 85% CI, 0.30 - 0.71; P for trend = .01). Milk was the dairy food that was most strongly inversely associated with the risk for colorectal cancer.

For cancer subsites, RRs were 0.37 for proximal colon (95% CI, 0.16 - 0.88), 0.43 for distal colon (95% CI, 0.20 - 0.93), and 0.48 for rectum (95% CI, 0.23 - 0.99).

"Our findings provide support for inverse associations between intakes of calcium and dairy foods and the risk of colorectal cancer," the authors write. "The associations did not vary significantly by subsite in the colorectum."

Study limitations include possible misclassification of calcium intake, and the possibility of unmeasured confounders accounting for the observed associations.

"Future studies should examine the relation of other components of dairy foods, such as conjugated linoleic acid, sphingolipids, and milk proteins, with the risk of colorectal cancer," the authors conclude.

The Swedish Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Research Council-Longitudinal Studies, the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (STINT), Västmanland County Research Fund against Cancer, Örebro County Council Research Committee, and Örebro Medical Center Research Foundation supported this study. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

In an accompanying editorial, James C. Fleet, from Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, calls this a powerful study with a large population linked to well-maintained, complete health records.

"Although this study offers some new insight into the dietary modulation of colon cancer, one is still likely to feel that this story has a lot more to reveal and that [this article] only begins to address these gaps," Dr Fleet writes. "Given that the interaction between vitamin D status and calcium metabolism is well established and that vitamin D status appears to modulate the effect of calcium on colon cancer risk, future studies on calcium or dairy intakes and cancer risk should not ignore it."

Dr Fleet has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:527-528, 667-673

Learning Objectives for This Educational Activity

Thursday, December 21, 2006

atrial fibrillation apirin atenolol

Atrial Fibrillation

What is atrial fibrillation (AF)?

Atrial fibrillation is a disorder found in about 2.2 million Americans. During atrial fibrillation, the heart's two small upper chambers (the atria) quiver instead of beating effectively. Blood isn't pumped completely out of them, so it may pool and clot. If a piece of a blood clot in the atria leaves the heart and becomes lodged in an artery in the brain, a stroke results. About 15 percent of strokes occur in people with atrial fibrillation.

The likelihood of developing atrial fibrillation increases with age. Three to five percent of people over 65 have atrial fibrillation.

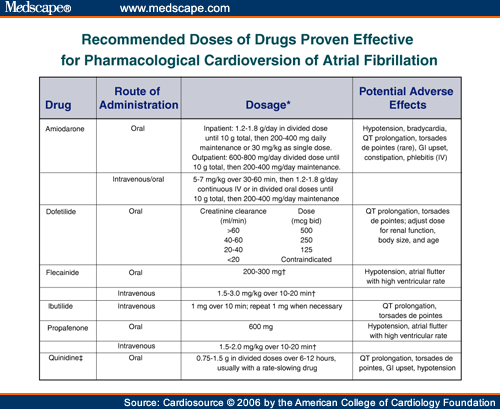

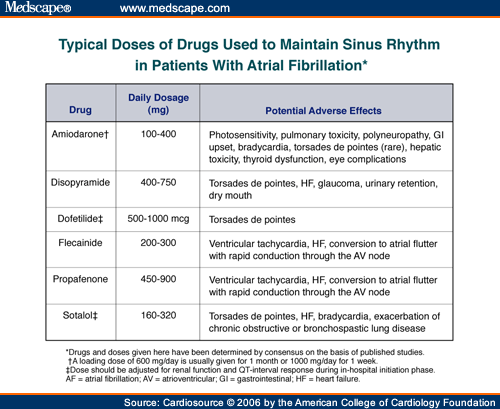

How is atrial fibrillation treated?

Several approaches are used to treat and prevent abnormal beating:

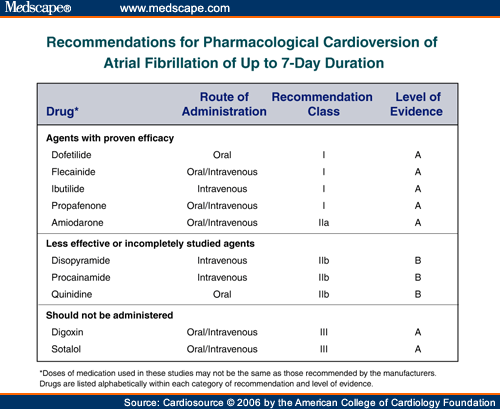

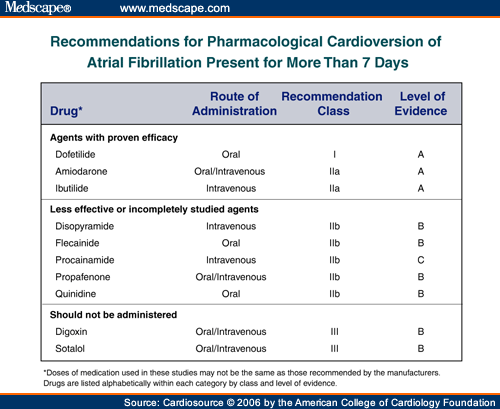

- Medications are used to slow down rapid heart rate associated with AF. These treatments may include drugs such as digoxin, beta blockers (atenolol, metoprolol, propranolol), amiodarone, disopyramide, calcium antagonists (verapamil, diltiazam), sotalol, flecainide, procainamide, quinidine, propafenone, etc.

- Electrical cardioversion may be used to restore normal heart rhythm with an electric shock, when medication doesn't improve symptoms.

- Drugs (such as ibutilide) can sometimes restore the heart's normal rhythm. These drugs are given under medical supervision, and are delivered through an IV tube into a vein, usually in the patient's arm.

- Radiofrequency ablation may be effective in some patients when medications don't work. In this procedure, thin and flexible tubes are introduced through a blood vessel and directed to the heart muscle. Then a burst of radiofrequency energy is delivered to destroy tissue that triggers abnormal electrical signals or to block abnormal electrical pathways.

- Surgery can be used to disrupt electrical pathways that generate AF.

- Atrial pacemakers can be implanted under the skin to regulate the heart rhythm.

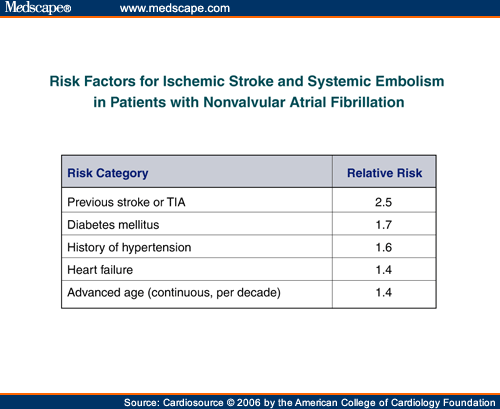

AHA Recommendation for Stroke Prevention

Treating atrial fibrillation is an important way to help prevent stroke. That's why the American Heart Association recommends aggressive treatment of this heart arrhythmia.

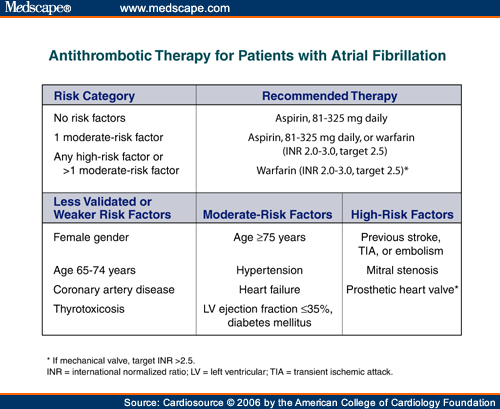

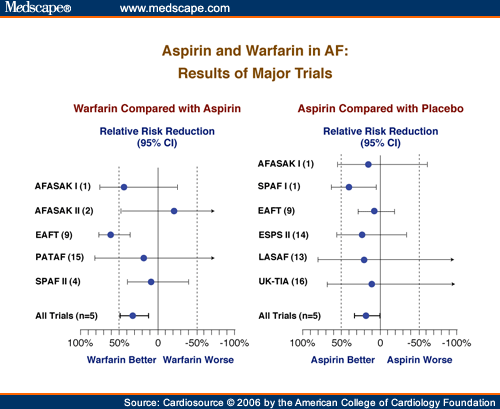

Drugs are also used to help reduce stroke risk in people with AF. Anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications thin the blood and make it less prone to clotting. Warfarin is the anticoagulant now used for this purpose, and aspirin is the antiplatelet drug most often used. Long-term use of warfarin in patients with AF and other stroke risk factors can reduce stroke by 68 percent.

- Physicians differ on the choice of drugs to prevent embolic stroke — stroke caused by a blood clot. It's clear that warfarin is more effective against this type of stroke than aspirin. However, warfarin has more side effects than aspirin. Examples include potential bleeding problems or ulcer.

- Patients at high risk for stroke should probably be treated with warfarin rather than aspirin unless there are clear reasons not to do so.

- Aspirin is the standard treatment for patients at low risk for stroke and under 75 years of age.

For stroke information, visit StrokeAssociation.org or call the American Stroke Association at 1-888-4-STROKE. For information on life after stroke, ask for the Stroke Family Support Network.

See the Related Items

arrhythmia

warfarin

|