Abstract and Transcript

Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia seen in clinical practice, accounting for approximately one-third of hospitalizations for cardiac rhythm disturbances. An estimated 2.3 million people in North America and 4.5 million people in the European Union have paroxysmal (self-terminating) or persistent (not self-terminating) AF.1

During the past 20 years, hospital admissions for AF have increased by 66%2 due to the aging of the population, a rising prevalence of chronic heart disease, more frequent diagnosis through use of ambulatory monitoring devices, and other factors.

AF is an extremely expensive public health problem (approximately €3000 [~US $3600] annually per patient)3; the total cost burden approaches €13.5 billion (~US $15.7 billion) in the European Union.

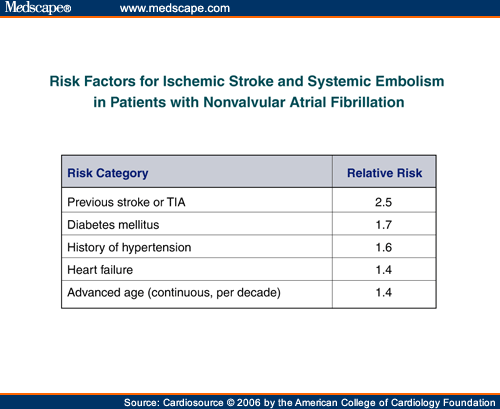

The risk factors for ischemic stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular AF are well established (Slide 1). However, while AF is often associated with structural heart disease, a substantial proportion of patients with AF have no detectable heart disease. Hemodynamic impairment and thromboembolic events related to AF result in significant morbidity, mortality, and cost.

In August 2006, the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) published a revision of the 2001 practice guidelines on managing patients with AF.4

The management of this complex and potentially dangerous arrhythmia includes prevention of AF, control of heart rate, prevention of thromboembolism, and conversion to and maintenance of sinus rhythm. The treatment algorithms include pharmacological and nonpharmacological antiarrhythmic approaches, as well as antithrombotic strategies most appropriate for particular clinical conditions.

There are important changes from the 2001 guidelines. The text of the 2006 revision has been reorganized to reflect the implications for patient care, beginning with recognition of AF and its pathogenesis and the general priorities of rate control, prevention of thromboembolism, and methods available for use in selected patients to correct the arrhythmia and maintain normal sinus rhythm.

Advances in catheter-based ablation technologies have been incorporated into expanded sections and recommendations, with the recognition that such vital details as patient selection, optimum catheter positioning, absolute rates of treatment success, and the frequency of complications remain incompletely defined.

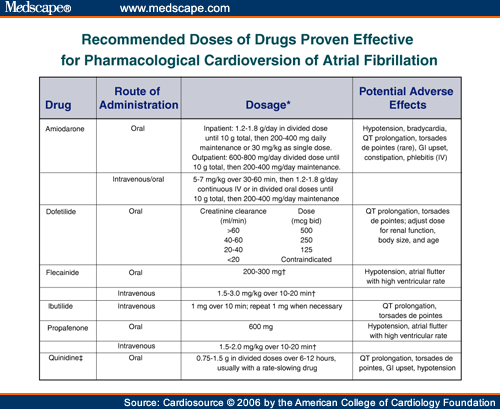

Sections on drug therapy have been condensed and confined to human studies with compounds that have been approved for clinical use in North America and/or Europe for pharmacological cardioversion (Slide 2) or maintenance of sinus rhythm (Slide 3) and their recommended doses. There are detailed recommendations, too, relating to antithrombotic therapy in patients with AF (Slide 4).

Accumulating evidence from clinical studies on the emerging role of angiotensin inhibition to reduce the occurrence and complications of AF and information on approaches to the primary prevention of AF are addressed, as these may evolve in the years ahead to form the basis for recommendations affecting patient care.

Finally, data on specific aspects of management of patients who are prone to develop AF in special circumstances have become more robust, allowing formulation of recommendations based on a higher level of evidence than in the first edition of these guidelines.

Overall, the updated guidelines are a consensus document that attempts to reconcile evidence and opinion from both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

This interview is with Hein Wellens, MD, emeritus professor of cardiology, University of Maastricht. A pioneer in "programmed electrical stimulation of the heart," in the late 1960s he and Rein Schuilenburg, MD, used catheters in a patient with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome to locate the origin of the arrhythmia and then a pacing device to initiate and terminate the arrhythmias.

Based on their work, stimulation studies could be combined with analyses of electrocardiograms to provide a noninvasive means of determining the origin of an arrhythmia. This paved the way for new therapeutic approaches, such as antitachycardia pacing, and advances in catheter-based ablation technologies.

The interview was conducted by Sidney C. Smith Jr., MD, FACC, FAHA, FESC, chair of the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines.

Transcripts

Dr. Smith: I am at the 2006 World Congress of Cardiology in Barcelona, Spain. With me is Hein Wellens, professor of cardiology at the University of Maastricht, Netherlands. We're talking about current issues in atrial fibrillation management. Professor Wellens, I've followed your work with great admiration over the years. Can you tell me how you see the field of atrial fibrillation today?

Dr. Wellens: It's a growing problem. The older population is growing and atrial fibrillation is typically a disease that becomes more and more prevalent with age. We have just received the new guidelines for management of atrial fibrillation, and in those guidelines we see - and I am very happy to see this change in emphasis - that the document is concentrating on the individual patient rather than on the electrocardiogram. So many different aspects: rate control versus rhythm control, prevention of thromboembolic situations, how to select antiarrhythmic drug therapy, when is a patient a candidate for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation? These are very well discussed in the updated guidelines and it's absolutely necessary for any physician looking after a person with atrial fibrillation to read them very, very carefully.

Dr. Smith: I think we ought to point out that these guidelines were produced by the ACC, the European Society of Cardiology, and the American Heart Association. So, they are going to potentially influence the thinking of many cardiologists around the world. What are some of the key changes in the guidelines? Are there any things that are new in terms of patient management?

Dr. Wellens: In recent years, we have read a lot about rate versus rhythm control, and that is one of the aspects of treatment that is very well discussed in the new guidelines. In terms of symptoms, rate control is typically considered for the patient who notices very little of the arrhythmia, while rhythm control is more likely to be applied to the person who notices immediately the arrhythmia and is experiencing consequences of the arrhythmia like shortness of breath, development of heart failure, etc. That's a major point if you are dealing with a patient who is tolerating atrial fibrillation very well; that's a patient for whom you should think about rate control.

Dr. Smith: One of the problems we face frequently with patients is that they have some impairment of ejection fraction - let's say 35% - and they present with new onset atrial fibrillation, they are short of breath, and have some left atrial enlargement. You recognize atrial fibrillation. Do you attempt rate control? Or do you try to go directly to cardioversion? And talk a little here about the remodeling that occurs.

Dr. Wellens: That's a very important point, Sid. As soon as atrial fibrillation occurs, you get electrical changes and contractile changes. The electrical remodeling involves shortening of the refractory period and loss of the relation between heart rate and duration of the refractory period. Also, as you very well know, because of atrial fibrillation the contractile behavior of your atria is lost.

These changes take some time, but they are usually complete after about a week. So the sooner you are able to convert that patient from atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm the better. It's very important to know that.

Also, pharmacologically, drugs that are able to successfully convert a patient when given within the first 24 hours, like flecainide, no longer work when the arrhythmia has been there for 6 or 7 days. So, the guidelines offer recommendations specific to how long the AF has been present (Slides 5 and 6). Similarly, if you want to convert electrically, the chance that you will be successful is higher when you are able to have that rhythm converted early after the onset of the arrhythmia.

Dr. Smith: Do you move fairly quickly to transesophageal echo? Where do you see the role for that in the time line?

Dr. Wellens: Transesophageal echo is important when you're not sure how long atrial fibrillation has been going on. It's also very important in the patient who has heart disease, because if there is an enlarged atrium, thromboembolic complications are much more common. So, in that situation, esophageal echo is a very important tool.

Dr. Smith: When you make the decision to cardiovert in your practice, do you find more often than not that it's electrical cardioversion? Or do you use drugs in many patients?

Dr. Wellens: You can use drugs if you are able to get the patient on the drug shortly after the onset of the arrhythmia. Like I said, flecainide works well when you give it within the first 24 hours. Other drugs - for example, ibutilide, a class 3 drug - work a little longer so you can still give it 4 or 5 days after the onset of atrial fibrillation. It all depends on the patient you have. Is it a patient who has no cardiac problems apart from the arrhythmia? Or is it a patient who has cardiac disease? What is the time frame from onset of atrial fibrillation to onset of treatment?

Dr. Smith: Let's talk about duration of anticoagulation after cardioversion. Let's say you cardiovert them and they are in normal sinus rhythm. How long do you continue anticoagulation?

Dr. Wellens: That's another important point that's well discussed in the new guidelines. It doesn't make any difference whether you have the paroxysmal form of atrial fibrillation or persistent atrial fibrillation; the risks of thromboembolic complications are similar. So, the duration and incidence of atrial fibrillation are not important in our decision making regarding anticoagulant therapy. That's a very important point.

Dr. Smith: What about the decision to use warfarin versus aspirin? Is this age related? Where do the new guidelines come down on this debate?

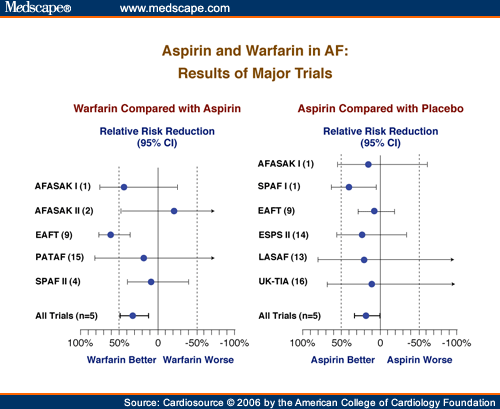

Dr. Wellens: Over the years, based on the results of a number of important trials, we have seen a reduction in the number of people we think can be treated with aspirin alone (Slide 7). The new guidelines clearly indicate that you should base the decision on the presence or absence of risk factors. If you have one risk factor, it is possible to put a patient on aspirin, but as soon as you see more risk factors - especially risk factors like a previous stroke or a transient ischemic attack, heart failure, or diabetes - then that patient should be on warfarin.

Dr. Smith: Age should be a consideration at some point too, correct?

Dr. Wellens: Yes, age is also important. If the patient is 75 years or older, you should not put them on anticoagulant therapy unless there is an additional indication, like valve replacement, for example.

Dr. Smith: Very quickly: catheter ablation. What's the role for catheter ablation?

Dr. Wellens: At this point, catheter ablation is very useful in the patient who has no heart disease apart from the arrhythmia and a normal size atrium. The problem is that we don't have long-term data on catheter ablation in sick hearts. That is a major point where we need more data because fibrosis formation is an important player in atrial fibrillation; we don't know how useful catheter ablation is in sick hearts.

Dr. Smith: It's been a real pleasure to have you with us on ACCEL and certainly this topic, atrial fibrillation, is increasing at near epidemic proportions. I suppose your final message would be for us to stay abreast of new developments, and particularly to take a look at the new guidelines that have just been released.

Dr. Wellens: I completely agree, Sid.

Dr. Smith: Thank you very much, Hein.

Guidelines: Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannon DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:e149-246.

Slides

Slide 1 - Risk Factors for Ischemic Stroke and Systemic Embolism in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation

Description: Data derived from collaborative analysis of five untreated control groups in primary prevention trials. As a group, patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) carry about a six-fold increased risk of thromboembolism compared with patients in sinus rhythm. Relative risk refers to comparison of patients with AF to patients without these risk factors. TIA = transient ischemic attack.

Citation: Reproduced with permission from Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannon DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:e149-246. Copyright of the American College of Cardiology.

Slide 2 - Recommended Doses of Drugs Proven Effective for Pharmacological Cardioversion of Atrial Fibrillation

Description: * Dosages given in the table may differ from those recommended by the manufacturers. †Insufficient data are available on which to base specific recommendations for the use of one loading regimen over another for patients with ischemic heart disease or impaired left ventricular function, and these drugs should be used cautiously or not at all in such patients. ‡The use of quinidine loading to achieve pharmacological conversion of atrial fibrillation is controversial, and safer methods are available with the alternative agents listed in the slide. Quinidine should be used with caution. AF = atrial fibrillation; BID = twice a day; GI = gastrointestinal; IV = intravenous. For the full list of references from which these recommendations are derived, please see the full text guidelines.

Citation: Reproduced with permission from Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannon DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:e149-246. Copyright of the American College of Cardiology.

Slide 3 - Typical Doses of Drugs Used to Maintain Sinus Rhythm in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation*

Citation: Reproduced with permission from Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannon DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:e149-246. Copyright of the American College of Cardiology.

Slide 4 - Antithrombotic Therapy for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation

Citation: Reproduced with permission from Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannon DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:e149-246. Copyright of the American College of Cardiology.

Slide 5 - Recommendations for Pharmacological Cardioversion of Atrial Fibrillation of Up to 7-Day Duration

Description: For the full list of references from which these recommendations are derived, please see the full text guidelines.

Citation: Reproduced with permission from Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannon DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:e149-246. Copyright of the American College of Cardiology.

Slide 6 - Recommendations for Pharmacological Cardioversion of Atrial Fibrillation Present for More Than 7 Days

Citation: Reproduced with permission from Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannon DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:e149-246. Copyright of the American College of Cardiology.

Slide 7 - Aspirin and Warfarin in AF: Results of Major Trials

Description: The image to the right shows the results of trials comparing aspirin versus placebo as antithrombotic therapy to reduce stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Although all six trials showed trends toward reduced stroke using aspirin, this result was statistically significant only in the SPAF Study, which was stopped at an interim analysis due to aspirin's efficacy. The graphic on the left compares adjusted-dose warfarin versus aspirin. The effect of warfarin on stroke versus aspirin varied widely among these five trials. No statistically significant heterogeneity was seen (p = 0.09), and meta-analysis showed that adjusted-dose warfarin reduced overall relative risk for all stroke by 36% (95% CI, 14% to 52%) compared with aspirin. Horizontal lines are 95% CIs around the point estimates. AFASAK = Copenhagen Atrial Fibrillation, Aspirin, and Anticoagulation Study (I and II); EAFT = European Atrial Fibrillation Trial; ESPS II = European Stroke Prevention Study II; LASAF = Low-Dose Aspirin, Stroke, and Atrial Fibrillation Pilot Study; PATAF = Prevention of Arterial Thromboembolism in Atrial Fibrillation; SPAF = Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study; UK-TIA = United Kingdom TIA Study.

Citation: Reproduced with permission from ACP-ASIM. Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, Pearce LA. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:492-501.